We are proud to announce the launch of the CREATIVE CARE COUNCIL! LEARN MORE

We are proud to announce the launch of the CREATIVE CARE COUNCIL! LEARN MORE

This article first appeared in the Maine Beacon. Read the original there.

The Maine senior population is set to increase by nearly 120,000 people over the next six years and experts are concerned about the economic impact that caring for this aging demographic will have on the state. From underpaid home care workers to working-family caregivers to small business owners who are struggling to support employees saddled with care obligations, there are many whose financial well-being is impacted by what has been described as a “broken system.”

Supporters of the Homecare for All citizens’ initiative, including experts and small business owners, are hopeful that the November ballot measure will not only help solve this multidimensional crisis but would also grow jobs and revitalize Maine’s “care economy.”

The universal program would be funded by closing a tax loophole that would impact the highest 1.6 percent of earners in the state. The Maine Chamber of Commerce and other opponents claim that lifting the Social Security cap on individual income above $128,000 and replacing it with a 3.8 percent tax would negatively impact employers as it would force “businesses to pay more to attract top talent” and would create “chaos” for the state’s economy.

But Stephen Campbell, a policy research associate with PHI, a research and analysis firm focused on solutions for eldercare and disability services, described Maine’s care economy as a “broken system” that is having a severe economic impact on workers, business owners, seniors, and individuals who have taken on the care of a loved one.

As Campbell explained, the state’s exploding senior population is in desperate need of more home health support, but individuals cannot afford the upwards of $50,000 a year that those services might cost. And despite the high-demand, homecare workers have little job stability and barely make above minimum wage, forcing many to leave the industry. To cope, friends and family members often end up taking on the care of aging loved ones—at the expense of their own time, financial stability, and the economy as a whole.

‘The sandwich generation’

Kennebunk resident John Costin, who owns the custom woodworking business Veneer Services Unlimited, has experienced the impact of this caregiving crisis as both an employer and family member.

Eight years ago Costin and his wife Rachel Phipps, a social worker, had her mother, Joan, move into a small guest house on their property. For years, her mother lived independently and was able to help with child care. But last November, she suffered a heart attack and suddenly required what Phipps described as “a high level of care.”

At the same time, one of Costin’s three employees also had to take a significant amount of time off—roughly 10 weeks in all—to care for his aging parents. Though he was able to keep his job, Costin said that his employee lost months of pay and, at the same time, it was a struggle for the small operation to “keep rolling and make our ends meet.”

“I try to be really flexible around time because I need that flexibility for my family as well. It’s kind of reciprocal,” Costin explained. “We’re that sandwich generation. Rachel has put in more of the time taking care of her mom but sometimes I have to be there for that and that affects me as a business owner. “

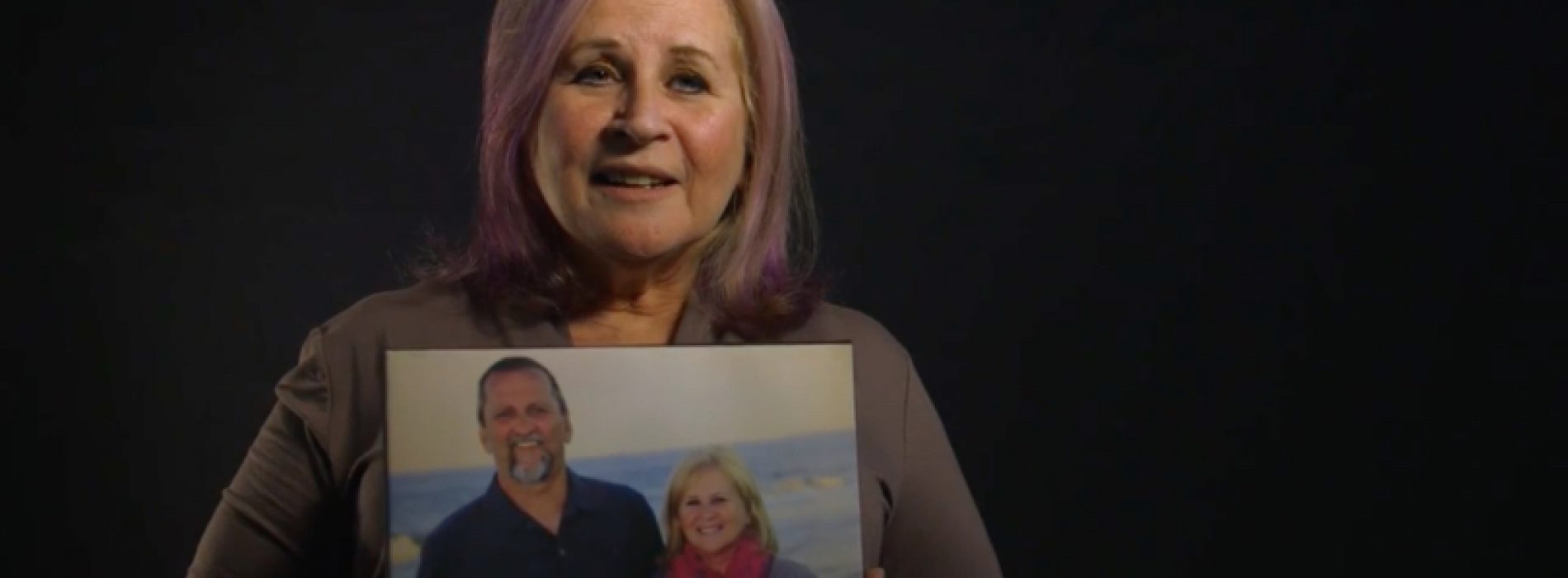

Debra Bourque of Biddeford also knows the economic toll of taking care of a loved one. After her husband Roland was diagnosed with early onset Alzheimer’s, Bourque tried to balance caring for him with the demands of her cleaning business by bringing him along to help.

As the disease progress and things got “increasingly more difficult for him,” Bourque said she would find him wandering away from the job site. “I was always on edge,” she said. Eventually, in order to stay home and make sure Roland was safe and cared for, Bourque was forced to scale back her business from five clients, working five days a week, to just two clients that she enlisted her son-in-law to cover.

“I went from never having to worry about money and putting money away every week to not putting money away and slowly digging into savings,” Bourque said.

These Maine business owners aren’t alone. According to a 2016 study by the AARP, 61 percent of working caregivers across the country have to rearrange their work schedules, take decreased hours, take unpaid leave, turn down a promotion, or leave work entirely. At the same time, this dynamic has cost U.S. businesses as much as $33 billion in lost productivity, when one calculates the cost of replacing workers, shifting employees from full- to part-time positions, missed work days and other workday adjustments, according to National Alliance for Caregiving.

“It’s difficult to balance both the economic stability of their own families with the care needs of their loved ones, friends, and neighbors,” Campbell said, adding that the situation underlines that fact that caregivers and seniors “aren’t getting access to the support that they need, which impacts their families but also the economy at large.”

Reviving the care economy

As Campbell noted, many unpaid family caregivers make these sacrifices because they are unable to afford or access the help of professional homecare workers. Paradoxically, low wages are driving unprecedented turnover in an industry with skyrocketing demand. According to PHI research, by 2024, Maine will need 1,630 new home care workers, which is more new jobs than any other single occupation. At the same time, the home care industry has reported annual turnover rates as high as two-thirds of the workforce.

Joanne Miller, who founded a South Thomaston-based homecare agency that she ran for years, said that the biggest challenge was always “finding workers, not clients.” Part of the problem, Miller said, is that home care is a “female-dominated industry” and that women have historically “kept house and tended to sick family members and done all that for free. “

“Every female dominated occupation is underpaid,” Miller continued. “Women are expected to take care of other people for free. People don’t think you need to pay for it.”

Home care workers in Maine are making $10-12 an hour, with annual earnings amounting to an average of $12,500 each year, according to PHI. Research shows that one in five homecare workers live in poverty and over half rely on public assistance.

At the same time, Miller added, “it’s not easy work.”

Campbell, who contributed analysis and research in support of the measure, says the Homecare for All initiative that will appear on the November ballot addresses this discrepancy and could dramatically transform the care economy in Maine.

“By rethinking the way we finance the system, and the way that we can elevate the professionalism of these careers and recognize the important role these workers play in a long term care system,” Campbell said, Maine can create a system that “puts the worker and the consumer at the center.”

When asked his thoughts on the homecare referendum, Costin said that he “really can’t see how it would be anything but beneficial.”

“When you lift that burden off workers and small business owners, when you have workers trying to make ends meet–—that’s huge,” he said. “Giving a decent living wage to the people doing that work, allowing people to stay in their homes, it’s all really beneficial to neighborhood stability and for local economies. I don’t really see the downside.”

Miller, too, said she’s “excited” about the referendum, adding: “The only way that we are going to fix the system which is slanted toward the wealthy is to become active voters.”