We are proud to announce the launch of the CREATIVE CARE COUNCIL! LEARN MORE

We are proud to announce the launch of the CREATIVE CARE COUNCIL! LEARN MORE

This article originally appeared in Foreign Policy on July 16, 2018. Read it there.

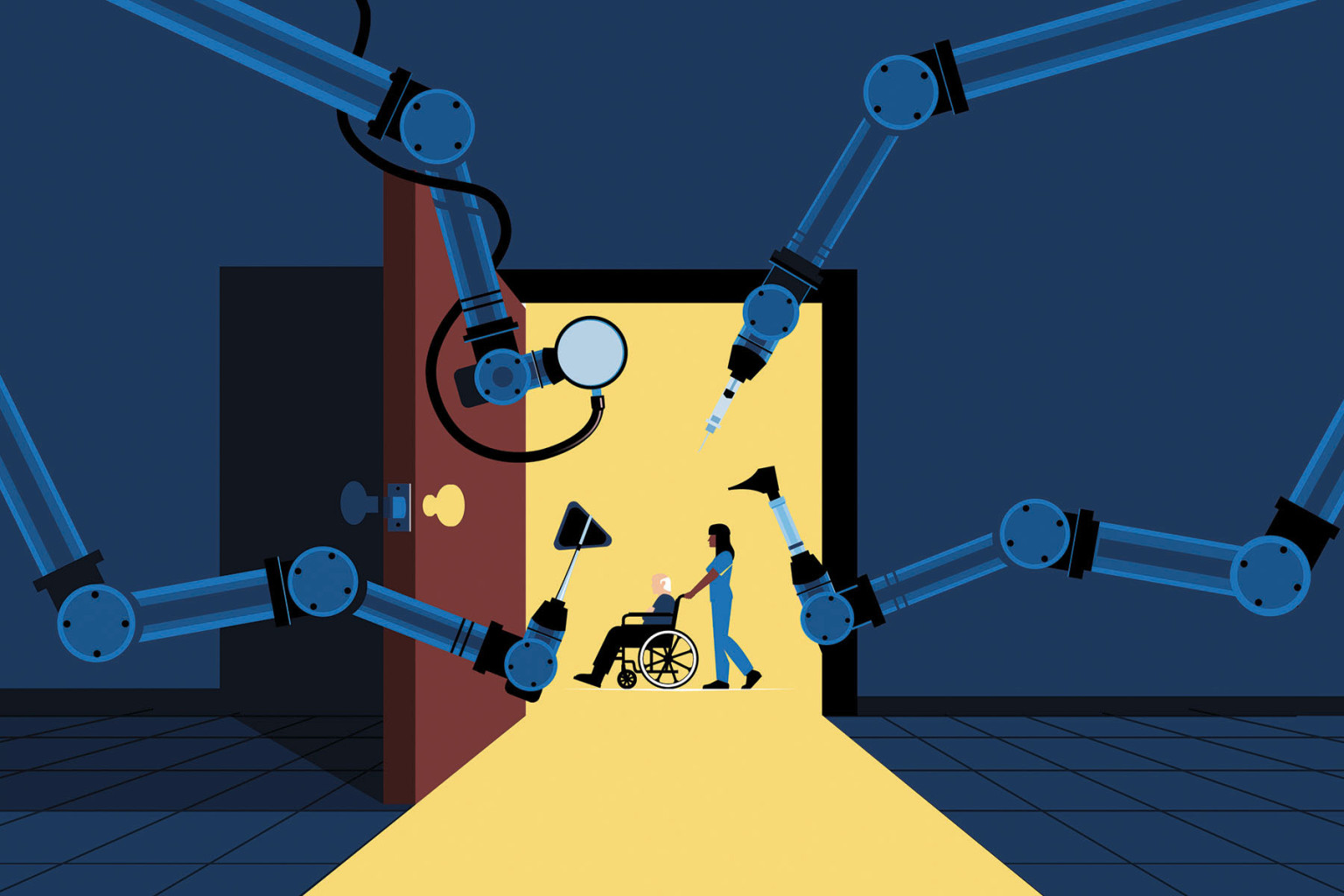

As automation grinds its way through industry after industry, some sectors still demand a human touch. Emotional skills and social interactions are far harder to mechanize than factory lines or even surgery. A recent McKinsey Global Institute report estimates that while most occupations could see at least 30 percent of their jobs automated, for home health aides or care workers, the figure is a mere 11 percent. It’s far easier to build a computerized driver than a robot nurse.

The work of caring for older adults and people living with disabilities is often physical — changing sheets, carefully lifting and washing bodies, monitoring and administering medication — but just as frequently emotional. Companionship and compassion are skills difficult to outsource or automate.

The harmful impacts of social isolation are widely known; one AARP study found that isolated older adults were 50 percent more likely to die over a six-year period than their more connected peers. In Japan, older people, particularly women, have gone so far as to commit petty crimes so they can go to prison for human contact and support.

While care work seems fairly safe from automation, however, it faces pressure from two other directions: an enormous surge in demand as developed societies age and the low regard most people have traditionally held for care workers themselves. By 2050, the United Nations projects that the world’s population aged 80 and over will triple. In the United States, 90 percent of people prefer to age at home, according to AARP surveys, and 70 percent of that group will need some form of long-term care. And all of these older people will need much more care. McKinsey estimates that these trends will create anywhere from 50 million to 85 million jobs in health care and other related industries in the next 12 years alone.

But care workers are already a vulnerable group — and, unless those vulnerabilities are addressed, the problem will only grow as the number of people employed in this industry increases. Historically, care has been seen as women’s work; it was long voluntary or unpaid and thus systematically devalued. Even today, most care workers in developed countries are still women and disproportionately women of color, migrant women, or women of marginalized social status. They often work part time and have inconsistent hours. In the United States, the profession’s historical associations with black women have led to harsher conditions and a deeper contempt. Long-standing racial exclusions from labor protections and a culture that has failed to adequately value or support caregiving have resulted in high turnover rates, worker shortages, and, ultimately, lower quality care. The median annual pay for home care jobs hovers around $13,000 in the United States — barely above the federal poverty level. As a result, more than half of all U.S. care workers rely on some form of public assistance.

These dire problems aren’t limited to the United States, however. In Japan, care workers commonly receive poverty-level wages and have unusually high rates of depression. In Germany, the care workforce lacks job security and is often underpaid.

Unless we raise wages for care workers, the entire sector will founder and grow even more unstable. If care workers continue to leave the workforce for better-paying jobs, those caring for family members will find it ever harder to both stay in the workforce and provide care.

The market is not going to solve these problems by itself. In the United States, where Medicaid is the largest payer of home- and community-based care, monopsony power and growing attacks on unions are making conditions for care workers worse, not better. In a fair system, the shortage of care workers would prompt employers to put a higher value on their labor. But the long associations of care with women, people of color, migrants, and other undervalued groups may put barriers in the way of market forces, leading to a situation where care workers are both underpaid and in short supply. Caregivers employed by individual families rely on the kindness, and whims, of their employers, with almost no one to look out for their interests and negotiate on their behalf. Finally, due to the complexity, fragmentation, and misaligned incentives of the current long-term care system, there is no guarantee that savings from home care in one part of the system — such as cutting Medicaid costs by keeping older adults out of institutional care settings — would go to improving the compensation of care workers.

Nor can women shoulder the burden they once did. Some 60 percent of families with children in the United States today rely on dual incomes, and, women’s rights aside, the cost of assigning care mostly to women would be too high. The average caregiver over 50 who leaves the workforce to take care of a parent loses $303,880 in lifetime wages, Social Security, and private pensions, kicking the costs down the line and making the economy as a whole less productive.

There’s no one easy answer for any of these issues, but a range of possible fixes do exist. Several countries have already strengthened their social safety nets in anticipation of the growing needs of their aging populations. Japan, where people aged 65 and older already account for more than a quarter of the population, instituted a public, mandatory, long-term care insurance system in 2000.

In 1995, Germany had already instituted a long-term care insurance system that provides both cash and direct service benefits to aging and disabled people, as well as free training on how best to manage cases and care coordination, all paid through the country’s comprehensive social insurance schemes. Other countries, including the United Kingdom and Italy, offer benefits or allowances to family caregivers, but the amounts are often too low or the qualifying requirements too high. Sweden’s approach has been to invest directly in the workforce, including investments of $114 million in training programs in 2011-2014 and $20.5 million in 2016.

Some countries are trying more diverse approaches. Japan recently, albeit quietly, loosened its notoriously stringent immigration policies to allow temporary low-wage migrant workers into the country, especially home care workers, to fill the gap. But these tentative, piecemeal approaches won’t do nearly enough to fully respond to the coming aging crisis or address the poor treatment of care workers.

An emerging model called universal family care, however, may succeed whether these other measures have not.

Universal family care is based on a social insurance model under which people share in the risks and draw on the benefits when they need them. The program builds on previous analogs, such as workers’ insurance, in order to rate caregivers’ — especially women’s — time and effort more fairly. It is also better adapted to the changing nature of work.

The program would provide a portable family care insurance fund that workers could take with them when they move from job to job. It would allow time away from work to care for an aging parent or provide the money to hire a skilled care worker, as well as pay for maternity leave and child care needs. The fund would support a living wage and increased access to benefits for care workers, in addition to training and career mobility, offering a path to the middle class.

Ideally, the fund would be integrated to address needs across our longer life spans — from child care to supporting a loved one with a disability to elder care. Such a program would be paid for at the national level but executed at the local level with families accessing community-based providers and resources. Ideally, local stakeholders, including workers’ representatives, would supervise implementation.

States such as Maine have already begun to experiment with key components of this idea, and the National Academy of Social Insurance, a leading nonprofit group in the United States, has launched a study panel to investigate funding and program administration options.

The money required would be substantial. There are many ways to potentially finance universal family care. One option would be to reduce the hundreds of billions of dollars wasted by health care systems on poor and fruitless end-of-life health care. Another option would be to allow Medicaid and Medicare to directly negotiate the cost of prescription drugs with pharmaceutical manufacturers, which would lower prices and thereby save some $100 billion per year, according to some estimates. Finally, if universal family care were actually implemented, the savings would increase. For example, according to MetLife, U.S. businesses could recoup the up to $33 billion per year in productivity currently lost by family caregivers who also work outside the home.

The future of work is care. Hundreds of millions of people will depend on the labor produced by a group that has all too often been exploited and abused. Making sure care workers have the skills, support, and pay they need to do the job right will pay off for everyone.